Over the last few months, we’ve come to establish something of a round robin routine at dinner. I ask, “What were the highlights and lowlights from your day?” and then we go around the table, everyone sharing their ups and downs. Last week, our older daughter reported a lowlight that got me thinking, again, about the ideas that are emphasized in schools as part of reading instruction.

Over the last few months, we’ve come to establish something of a round robin routine at dinner. I ask, “What were the highlights and lowlights from your day?” and then we go around the table, everyone sharing their ups and downs. Last week, our older daughter reported a lowlight that got me thinking, again, about the ideas that are emphasized in schools as part of reading instruction.

“I had to stay in from recess because I haven’t met my AR goal for the month,” she said.

AR is Accelerated Reader, a software program that my daughter’s school uses to measure students’ reading comprehension skills. When students read AR-endorsed books, they take an online test which, ostensibly, shows how much they understood about the book’s content. Students progressively set and work toward higher reading goals each month — reading more challenging texts and scoring higher scores — and the software provides an easy-to-interpret graph of how well students performed on the tests. These data are then used to make inferences about students’ reading skill levels.

“Hmmm,” I said. “Doesn’t your teacher know that you’re already a pretty confident reader?” I asked. “At our parent-teacher conference he expressed no concerns about your reading.”

“Ya, Mom,” she replied. “But the State of Michigan requires us to do these AR tests, so I have to do it.”

“Hmmm,” I said again, knowing full well that the State doesn’t mandate the use of any particular program, but also aware of the ways that each school is held accountable and must document improvement. “Don’t you think it’s more important for you to have a little outside time so you can get some exercise? Exercise makes your brain work better, you know. If you had recess, your reading would be even better.”

By this time, our younger daughter had already interrupted with news of her day which featured a field trip to sing Christmas carols at a local retirement center.

Later that evening, catching up on my FaceBook news feed, a colleague and friend who, last week, led the study group on graphic novels at the Literacy Research Association conference posted:

“In the car after picking up the big one, “so mom, I have to redo my ‘pages read’ report. My teacher said graphic novels and audio books don’t count.” My head almost exploded.”

Again, I said, “Hmmm.”

On the same day, in Massachusetts, where her son attends school, a teacher said that pages read need to be counted, and that graphic, multimodal pages don’t count. In Michigan, where my daughter attends school, a teacher said that reading to take a computer test was a more important priority than getting fifteen minutes of fresh air and exercise.

At that moment, I felt a bit disheartened that the research that could inform teachers’ instructional choices around reading seems to have been trumped by something else. That something else, seems to be the need to account for very particular skills in very particular ways. To me, the accounting in both of these cases seems to have been driven by simple views of reading that could, in fact, undermine students’ growth and development as readers.

Here’s why I think this.

First, my colleague’s research (Jiménez, 2014) has shown that the expert construction of meaning from graphic novels is a very complex cognitive process, requiring sophisticated, flexible integration of print-based and visual literacies strategies. Telling students that “graphic novels don’t count” privileges print-based literacies that, although obviously important, are not the only literacies that children need to develop. In a world where texts have become increasingly multimodal, especially online, does it not stand to reason that children should practice the construction of meaning from visual, auditory, and print-based texts?

Second, my own work has investigated the contributions of executive functions to reading comprehension — they’re sizable, as has been shown by more than 30 years of research by scholars all over the world (e.g., Daneman & Carpenter, 1980; Keiffer, Vukovic & Berry, 2013). Individual differences in inhibitory control, set-shifting and working memory correlate positively with individual differences in reading comprehension. Adele Diamond’s work tells us that physical activity supports children’s development of inhibitory control, the ability to switch between sets of information, and use working memory (e.g., Diamond & Lee, 2011). Together, these lines of research show that children who have better executive functioning tend to be better readers and that children who exercise have better executive functioning. A study by Reynolds, Nicholson & Hambly (2003), for instance, brings these ideas together. Their research showed that children diagnosed with dyslexia, made statistically significant gains on reading comprehension measures when they exercised their bodies. Children who used a balance board, practiced throwing and catching bean bags and engaged in various stretching and coordination exercises over a period of six months showed greater reading gains than a control group who did not exercise systematically. Although this research focused on children with particular reading pathologies, the fact that exercise enabled growth on reading comprehension measures for the children who struggle most to construct meaning from printed texts suggests an important mind-body link that, I would argue, teachers should consider.

I think it is important to note that I know these two teachers in MA and MI are operating in a time of incredible constraint, and that their directions to students are surely motivated by a desire to support reading growth. Teachers do this work because they care about students in every way — I would never question this. And yet, the push for teachers to show the impact of their work in ways that can be measured may influence their choices about which kinds of texts get privileged, or how students are asked to use their time.

Given the research that I’ve summarized above, I think it’s time, actually, for teachers to push back and use expanded notions of the kinds of activities that will support reading gains. I think it’s time for teachers to push back against views of reading in school that privilege the printed word. Multimodal text pages should definitely count. In fact, as my colleague’s research has shown (Jiménez, 2014) graphic novel readers may be engaging even MORE cognitive processes as they construct meaning. I also think it’s time for teachers to embrace the complexities of reading as an embodied process that improves as children’s whole bodies are nurtured. Recess may actually be the most important 15 minutes of the reading curriculum each day.

References

Daneman, M. & Carpenter, P.A. (1980). Individual differences in working memory and reading. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 19, 450-466.

Diamond, A. & Lee, K. (2011, August). Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science, 333, 959-964.

Jiménez, L. M. (2014). Out of the box: Expert readers allocating time and attention in graphic novels. [Dissertation]. Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertation Abstracts International, 74:8. Dissertation ID: DA3560470.

Keiffer, M.J., Vukovic, R.K., & Berry, D. (2013). Roles of attention shifting and inhibitory control in fourth-grade reading comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(4), 333-348. doi: 10.1002/rrq.54

Reynolds, D., Nicholson, R.I., & Hambly, H. (2013). Evaluation of an exercise-based treatment for children with reading difficulties. Dyslexia, 9, 48-71. doi: 10.1002/dys.235

You can read more about Dr. Laura Jiménez’s work at her blog.

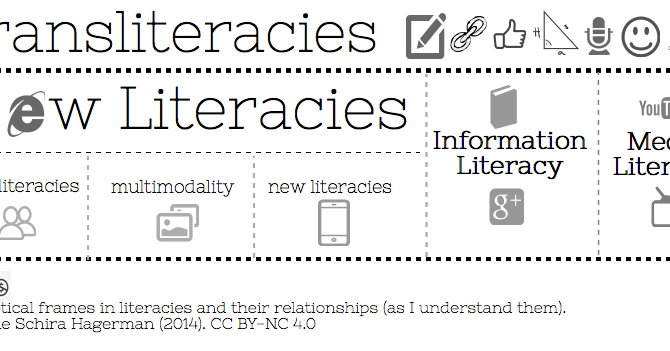

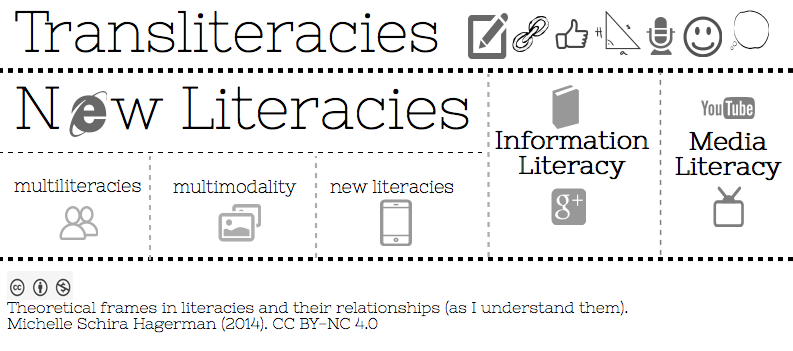

This week, I’m presenting at a two-day workshop for the Association of Independent School Librarians. The title of the PD session is “At the Center of IT All: Scaffolding Advanced Information Literacies for K-12 Students in School Libraries”. One of the questions that the AISL wanted to explore through this PD session is one that many literacies scholars grapple with daily — how do theoretical frames such as transliteracies, New Literacies, multiliteracies, media literacy, and information literacy fit together? And to follow up on that question — how are these theoretical frames both similar and different?

This week, I’m presenting at a two-day workshop for the Association of Independent School Librarians. The title of the PD session is “At the Center of IT All: Scaffolding Advanced Information Literacies for K-12 Students in School Libraries”. One of the questions that the AISL wanted to explore through this PD session is one that many literacies scholars grapple with daily — how do theoretical frames such as transliteracies, New Literacies, multiliteracies, media literacy, and information literacy fit together? And to follow up on that question — how are these theoretical frames both similar and different?